In Lock-Up OR Tied-Up: Baduanjin (Eight Brocade Exercises) Used as a Therapeutic Intervention

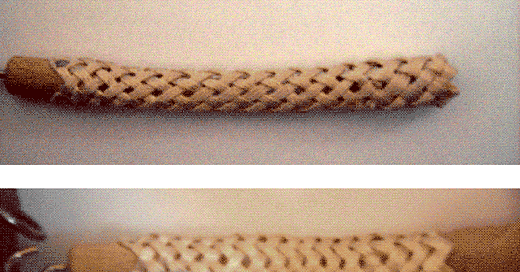

Baduanjin (八段錦, ‘eight brocade exercise‘) is a classic system of Chinese physical culture.1 Such systems are generically, if not totally accurately, called qigong. There are an almost innumerable number of qigong sets that integrate, in different proportions, breathwork, stretching, physical exercise and meditative practices. Some are crafted to enhance health; others are for the purpose of developing power or martial arts abilities. Each set can have quite different effects on body and mind. Baduanjin is known to enhance skeletal-muscular fitness and vascular health, as well as enabling practitioners to modulate and control their emotions (Cheng 2015).2 The term ‘brocade’ can be interpreted in a variety of ways. One that the author finds most useful is that ‘brocade’ refers to the body‘s web of connective tissue (fascia, ligaments and tendons). These are stretched and strengthened through the integration of specific physical movements with certain breathing techniques. A useful image for this is a Chinese finger trap, a tube of woven bamboo strips, that is inserted on the ends of two fingers or similar objects, and locks which becomes rigid when pulled, thereby tightening the weave of the bamboo strips.3

There are a number of variations of baduanjin, both standing and sitting . The set that I have used both for personal physical cultivation as well as in my clinical practice is a standing set, that has the following exercises. [(NOTE: The linked video is somewhat different from the way I practice these exercises, but will give the reader a general idea of what it is like].

Two Hands Hold up the Heavens

Drawing the Bow to Shoot the Eagle

Separate Heaven and Earth

Owl Gazes Backwards or Look Back

Sway the Head and Shake the Tail

Two Hands Hold the Feet to Strengthen the Kidneys and Waist

Clench the Fists and Glare Fiercely

Bouncing on the Toes

A comprehensive discussion about baduanjin would require a book, and the author(s) would need to be fluent in Chinese, not only modern, but classical as well. To do justice to the topic, such a work should include a history of physical culture in China, as well as a discussion of the proto-scientific theories that underpin these exercises. It would then be necessary to discuss the physical and psychological effects of the performance of baduanjin, comparing it, in general, to other systems of physical culture, and more specifically, to other forms of qigong. Such a study would be further complicated by the variety of exercises, both sitting or standing, that can comprise a baduanjin set, as well as the different ways that practitioners are taught to execute them. Finally, such a study would, by necessity, investigate the research used to establish or debunk whatever claims are made regarding the merits of the practice.

I am not the man to undertake such a work. Instead, I am going to discuss several cases where I used baduanjin as a method of psychological intervention. They will be, in essence, phenomenological case-reports. Phenomenological accounts can be of considerable value, because they often bring new, unexpected information. All too often, researchers search for confirmation of what they already expect to be true. Phenomenology introduces us to the unexpected, offering new directions for research concerning areas of human existence that have not been thought of before.

In Lock Up

Approximately thirty years ago, I worked at a community mental health agency, specializing in crisis intervention. The local youth detention facility contacted my supervisor and outlined the following problem: The facility functioned as a jail for youth under the age of eighteen. They had forty single-bed cells, holding youth as young as twelve, detained for misdemeanors like truancy, vandalism and petty theft, as well as those either awaiting trial or placement after conviction in a long-term facility for serious drug dealing, rape, assault and murder. Some of the kids were on suicide watch, which meant their cell was totally stripped down to a mattress on the floor and there were fifteen minute checks by staff to try to ensure the youth didn’t try to kill himself or herself. The kids were about ninety percent male, and a number of them were gang affiliated, divided among Crips and Bloods (which were, perhaps surprising to some of my readers, multi-racial) and various Hispanic gangs.

The detention facility generally had between seventy and eighty young people at any time. “Wait a moment,” the reader might ask, having read the number of forty single-bed cells. Too few beds, too many kids. The overflow slept on mattresses in the hallways. The director described the facility as ‘hot,’ meaning that there were frequent conflicts between inmates and staff (called ‘counselors,’ as is customary in youth facilities, rather than ‘correctional officers’) as well as fights among the youth themselves. The director requested that mental health specialists be dispatched to the facility to conduct twice-a-week group therapy sessions to lower the ‘heat‘.

Another therapist, Carola Schmid and myself, were each delegated to separately conduct such therapy sessions. They were a disaster. No one talked. What would they talk about anyway? Their crimes? Other people’s crimes? Their gang affiliation or their conflict with other gangs? Each of these subjects would have put them at either legal or physical risk. How about talking about their insecurities, their fears, their loneliness, or their traumas? What do you, the reader, think would happen to any youth who exposed his or her vulnerability within a group where some were predators, and others would willingly lend themselves to pack aggression, if only to keep the mob’s attention away from them? Any jail or prison community is a dominance hierarchy, and self-disclosure would be the same as painting a bright blue spot on a magpie’s neck— all the other birds in the flock would peck at it until the bird was killed.

There were other problems. The population was not stable. Some youth were quickly released—their minor misdemeanors attended to by family, attorneys or probation officers. Others were hospitalized due to complications from drug abuse or mental illness. Others had their crimes adjudicated and they were transferred to other facilities. There was stress among different ethnic groups, different gangs, and the rare girl in the group would, just by her existence, precipitate macho posturing, roughhousing, clowning around or sexual harassment. [And interestingly, staff found the teenaged girls among the most difficult to deal with. Sometimes, they were the instigators of violence, and they generally had no ‘off switch.’ As one counselor said, “The boys know the rules. They will front staff, maybe even take a swing, but once it goes hands on, it’s kind of a fight with rules. The boys know when to give up. With the girls, they don’t know when they are losing and they somehow don’t realize that we are holding back, trying to control them without hurting them: they scratch, bite, go for the eyes. The worst is when you try to get them back in their cell and they starfish in the entryway. You pry off one limb and the other three lock on somewhere else, and everyone is cheering the girl, and she’s screaming and we look like idiots.”]

Having experienced a total failure in our attempt to set up therapy groups, Ms. Schmid and I came up with an alternative that we proposed to the facility director and our supervisor. She is an expert at Ashtanga Yoga, a very powerful, dynamic form, sometimes referred to as ‘power yoga,’ and I am an expert instructor of traditional martial arts. We proposed to go there, alternating on a weekly basis; she would teach yoga and I would teach baduanjin. As I did not attend Ms. Schmid’s classes, I cannot report in detail on her success, but in our regular conversations, she clearly had much the same effect on her classes as I did. (In some respects, Ashtanga Yoga works the body in the same way as baduanjin, but in a much more extreme fashion).

Ms. Schmid writes of her own classes: “On one occasion, I wanted to teach them handstands without the wall, so I asked them to get in groups of three, so two people could help/spot the person going in the handstand. There was some reluctant movement and then one kid said, ‘No fucking way,’ which seemed to be what all the other kids were thinking. I asked why, to which he replied ‘I don’t fucking trust anyone in here.’ They agreed that they would all try if I was one of the two people helping/spotting, and we worked our way through the group.”4

As to my own work, please remember that each class would have about 70% new members. Those who were there on a regular basis were awaiting trial on felony charges. Each session, therefore, required an introduction. We would meet in an open space, much like a volleyball court, myself and about fifteen to twenty youth. After a brief introduction, invariably, one young man would ask, ”So, are you going to teach us to kick ass?”

My reply was always the same: ”You don’t know how to do that? You need some old man to teach you?” I would say this with a smile, so the kid was teased by his comrades, but not shamed. I would then continue: ”You really think I would teach you anything that would make you a better fighter? I am doing this for a living! This is my job. I don’t even know you guys. If I teach you something that makes you a better fighter and you get out and jack somebody up, then what’s the newspaper going to say? ‘Youth taught martial arts at Thomas Abernathy Youth Center, arrested in assault.’ I’d lose my job. I’m not going to lose my job over you guys!”

This would break the ice. Some kids would laugh. Most would smile. Then, ”So let me ask you a question. Don’t you hate it when someone makes you mad? There you were, minding your own business, having a good day, and someone makes you mad: you lose your temper, and maybe you end up doing something you didn’t plan to do, maybe not even want to do. Maybe that’s why you ended up here. Well, I’m going to teach you some exercises that have the possibility of altering your mind, so that other people won’t be able to make you mad. You’ll only get mad when you want to be mad.” And then we would begin.

Perhaps the reader might ask why I didn’t explain the negative consequences of anger in one’s life, or how these techniques would help one control one’s temper and not get angry at all. That would be naïve. These youth lived in a world of power, obsessively focused on dominance hierarchies within their own small societies, both with the detention facility and outside it as well—in many, if not most cases, this included their families. Any admission that they needed help being less angry would appear to others as weakness. As one young man said to a therapist-associate of mine, ”Ma’am, that sounds really nice, what you are saying about anger, how it hurts me, and how I should, what did you say, ‘Let go of your pain, watch it pass, and be able to forgive the person who hurt you.’ But if I tried what you are saying—and it worked—I wouldn’t last a week in my neighborhood.”

Every once in a while, a young man would test me. He would start clowning around, bothering others, maybe posturing up to me. I’d send him away from the group, calmly, without rancor, saying something like, ”We’re here to work. You aren’t working here. You have to go back to your cell. Tell the counselor over there.” This was very important for all the young people in the group. That youth was the emissary of all the kids, whether he knew it or not, because everyone there had a question: ”Can we make you mad?” If they could, then nothing I might present offered them a thing—they would see me as just another version of themselves—a full-grown wolf lying to a pack of wolf-cubs. I wanted to show them something else: that fully developed humans possess their emotions, rather than emotions possessing them.

The results of this training were clear. After a year of the program, Ms. Schmid and I were told that critical incidents were down fifty percent, even though no other changes had been made within the facility. Was it the baduanjin? Or the yoga? Or both? Or was it something else as well—Ms. Schmid and I embodying, literally, calm and dignity in the context of powerful trained movement. Young people could associate the way we presented ourselves as an exemplar of something they wished to become. It is my best guess that Ms. Schmid and I had a synergistic effect, at least with the inmates who attended both of our classes. She is a powerful but kind woman, and treats people in a very similar way as I do: frank and direct, never ingratiating herself to be liked. I think that, for the youth, getting the same ‘model of adulthood’ from a powerful man and a powerful woman was very positive.

However, beyond modeling, what specifically did baduanjin offer these young people? There are many ways to execute these exercises—they can be executed in a very relaxed manner, much like taijiquan, for example. I deliberately taught them in a way that required the practitioner to tense to the degree that they were ‘intolerable.’ Then, they would continue the movement progressively relaxing. Finally, when relaxation became ‘intolerable,’ the practitioner continues the cycle of the movements, incrementally increasing the tension.

My intention was that these youth would have the experience of managing tension and release within their bodies, according to their will. The mind and body being intertwined in an inextricable braid of experience, this would reverberate into ‘tension’ and ‘release’ within their thinking processes and emotional reactions. For example, if, in the middle of an exercise, a young person had a troubling thought, giving rise to a troubling emotion, he or she could change his or her somatic state at will, and notice the ebb and flow of his or her cognitive and emotional processes. By doing this by himself or herself, the young person was not dependent on another person for his or her sense of well-being or threat. Finally, because these exercises were associated with martial arts practice, these young people, obsessed with power, were able to separate what they were doing from other activities that might offer the same benefits, but were unacceptable due to their culture (that of youth who saw themselves as outlaws).

Enough theory. How did this work in practice?

Angel

There was a young man who attended my classes for a span of some months. He was golden-skinned, tall and lean, with long raven-black hair. His name was Angel. He never spoke to any of the other boys, walking among them like a panther through a mob of yard dogs. He always took a position at the periphery of the group, as far away from me as he could get—but he never took his eyes off of me. He did the exercises meticulously. After some weeks, I asked staff about him. ”He beat an old man nearly to death, a Korean War vet—he was in a coma for months—and Angel was tried as an adult. He got twenty-five years. They are just waiting for a bed to open in the youth offender wing of the prison where he’ll be kept until he is eighteen; then he’ll be transferred to general population. Be careful of him—he’s the most dangerous kid in here.”

One day I arrived and one of the staff told me, ”Angel is going up today.” I nodded and went to class. Angel was there, silent, doing the exercises, meticulous as always. When the class ended, contrary to his habit, he lingered until everyone else had left. Then he walked towards me, slowly, his eyes fixed on mine. It looked like he was preparing to confront me physically, but at the proper distance, he veered off at an angle and paused, still looking me in the eyes. I said to him, ”Where you are going, control of your emotions is the only thing that will save your life. Do your time and get home.” He walked past me, and over his shoulder, he whispered, ”I wish you were my dad.”

Boyd

In the later months of that year, there was another youth who was also a frequent attendee, named Boyd The other boys stayed away from him too, but it appeared more revulsion than the wary respect with which they treated Angel. Boyd was pale- skinned, with crinkly red hair. I have noticed that, contrary to my own youth, young men of recent generations are more physically modest in certain settings, jail being one of them. Every youth kept his shirt on, despite the muggy summer heat—Boyd was the one exception.

It may sound cruel, but he was an odd boy. He held eye contact way too long, and he did the baduanjin exercises over-exuberantly, trying to flex his skinny half-naked body, trying to draw attention to himself. The other youth did not know his crime, but they knew . . . something. He gave them the ’creeps.’ He, too, was awaiting placement in a facility, one that had special treatment programs for ‘sexually aggressive youth.’ He was fourteen years old, and he had molested his nine-year-old sister for many months. He was caught when she disclosed the abuse to their mother.

One day a counselor told me that Boyd would not be attending the training group, that he was suicidal—he was going to be sent to the specialized facility in a few days. He was confined to his cell on suicide watch After class, I asked if I could visit him. His cell door was open, and his mattress was on the floor, with all bedding stripped away. Anything that he might possibly use to harm himself had been removed from the cell. He was lying on the mattress, staring at the ceiling. I asked if I could come in, and he silently refused, shaking his head. I said, ”It’s your house, and I’ll respect that. I have just one thing to say, and then I’ll be on my way . . . Boyd, I’m glad you are feeling suicidal.” His eyes widened and he turned to look at me. ”Don’t get me wrong, I don’t want you to kill yourself. But I’ve been told what you did. And if you didn’t feel bad about that, there’d be no hope for you. That you feel suicidal gives me hope. It suggests the possibility that you know right from wrong, that you feel bad about what you have done, and if you choose, you can work very hard to be different so you don’t have to feel like you do now . . . .” His eyes full of unshed tears, he gave me the slightest of nods, and I said goodbye and left.

The next time I went to the facility, they told me that Boyd had been transferred, but that he left me a note, sealed in an envelope. I could read it, but it had to go in his file afterwards.

Dear Mr. Amdur, I know what I want to do. I still want to do it. All the time. But it’s wrong. I know it’s wrong. But I think I’ll always want to do it. So I was thinking, I’m going to be at Blue Mountain for a few years. I decided that I am just going to stay in my cell and do those exercises you taught, all day. Every day. And maybe, even though I want to do it, those exercises will give me the power so I don’t do what I want to do.

Tied Up in Knots

The subject matter of the following section may be a little shocking to some, as it concerns an individual who was part of a rather complicated relationship, involving several people with what may be, to many readers, rather unusual sexual preferences, involving what is often referred to as BDSM (bondage-discipline sado-masochism). So, let me preface this with a statement. This incredibly broad area of sexual practices can draw people with various, sometimes quite severe, pathologies that involve a desire to have power over other people, and through this, giving them an opportunity to cause others harm in both emotional and physical ways. On the other side of that ‘equation’ are some people who have a pathological need to be degraded and hurt.

On the other hand, other people, most, in my experience, turn their unusual desires into power-exchange activities—they explore their own limits in terms of being given permission to have power over another individual, or allow another to have power over them. Their activities are consensual, and there is mutual concern and solicitude, even when engaged in activities that may be intense, apparently degrading or even painful. Among this latter type are people I think of as alchemists: they take their own history, their own trauma, and re-experience what hurt them in a controlled way where they have ultimate power of the situation. They can stop it at any time. In doing so, they turn painful experiences into pleasure, or another form of ecstasy or transcendence. Thereby, what once had power over them no longer does. However, sometimes people can get locked into such an activity without mindful awareness of what they are doing—it can become a compulsion that circumscribes their sexuality or the type of relationship they engage in.

To give a little context to this account, I never had an office. I saw people in their place of residence or elsewhere: I’ve met people escaping from violence in public libraries, or in the lobbies of police stations, and I used to meet one young man on a large boulder beside the ocean. Why did I doing things this way? I only worked with a few people at any given time, because I had a variety of other types of work that I did (you may infer, correctly from the tense I am using, that I’ve retired). Beyond that, I’ve always believed that seeing people on the territory of their choice made me a guest—they invited me into their lives to help them, and they could tell me to leave at any time. Finally, there is so much that you can learn about a human being when you are in their space, or at a space of their choosing.

I was called to the home of a woman who was well-known (in certain circles) as a master of a sexual practice called shibari (縛り). It is derived from medieval Japanese police practices—people taken prisoner by police were bound with cord in elaborate patterned knots, depending on their social rank and caste. One could instantly tell a prisoner’s station in life by how they were bound. Some of these bindings twisted the limbs—in fact, some were used as a form of torture. At some point in time, an erotic version of these ties and binds was developed, referred to as kinbaku (‘tight binding’ 緊縛). Shibari, a generic term for tying things up, became common in the West to refer to this type of sexual practice.

The woman who called me, Gloria, was married to one man, and had three lovers: two, who lived elsewhere, and Naomi, who also lived in the house. All of them were polyamorous: they had a number (actually, a vast number) of agreed-upon rules concerning how their relationship(s) were structured to minimize jealousy and other stresses on this complex arrangement.

Naomi was in a pseudo-slave role in the home. She wore a leather collar that was locked around her neck with chain links. She sometimes slept in a small cage in the same room as Gloria and her husband. One of her most important roles was that she was a shibari model: Gloria, a very important figure in that particular city’s BDSM community, would give public exhibitions, tying Naomi up in intricate contorted poses, suspending her above the ground. Naomi was as powerful and strong as an Olympic gymnast. And she was suicidal.

Gloria explained all this to me in her beautiful living room. The windows were spacious, overlooking a garden with bonsai and topiary, the sun streaming through the glass. Also in the room was Naomi. She was almost six feet tall, with a spiky blonde haircut. I could see her slave collar, black leather and silvery chain links, with a small padlock at her throat. She was also wearing a floor length camel-hair trench coat on this hot summer day, and she was shivering with fear. She had misinterpreted what Gloria had told her before I arrived, and she believed I was there to take her away to a psychiatric hospital. Gloria was wringing her hands in concern for her—there was clearly a strong, loving bond between them.

I explained to Naomi that I had no power to take her anywhere, and that as long as she was not intending to kill herself, and only had strong thoughts and desires to do so, we could work together therapeutically. I told her that I very much wanted her to tell me if she intended to kill herself, so I could get her help. But as for her thoughts, even her intentions, those were things we could talk about. She agreed to work with me. Then I said to Gloria, “Thank you for introducing us. But from this point on, my conversations with Naomi will be strictly confidential. Would you kindly leave us alone.” Gloria stood up, kissed Naomi on the cheek and left the room.

I wanted to meet with Naomi elsewhere. I had just met them, and I had been fooled before by the appearance of love and affection between people. I did not know if Naomi was being abused, or if she was in a toxic relationship, one that was damaging her (This would be an easy assumption to make, of course. I wouldn’t be surprised if some of my readers have already decided that was so). One of the best gifts that my training in phenomenology gave me was the concept of ‘bracketing,’ the skill of being mindful of one’s reactions, assumptions, past knowledge and prejudices, and bracketing them off to the side. If they prove to be true, one can always return to them, avail oneself of what they have to teach. But through bracketing, one suspends all this, as if leaving them in a cloud, hovering nearby, and one strives to see the person and situation as they truly are. The ‘weight’ of conversing in Gloria’s home did not bode well for an effective therapeutic relationship. Upon my asking, Naomi told me that she had her own apartment, where she lived a couple days every week. And after she agreed to do nothing to harm herself until we met again, we made an appointment three days out.

Our subsequent meeting left me puzzled. Naomi told me she had no history of abuse growing up, either family or otherwise. Her mother and father were benign hippies, who loved to garden and donate their time to a variety of social justice causes, and her brother and sister were typical Pacific-Northwest-Liberal-Americans. Naomi had always been different.

She was besieged by a variety of obsessive-compulsive symptoms, where she would feel an internal demand to do something: leap seven steps down to the pavement, spin four times on a street corner, or jump up and touch a street sign. And if she didn’t do it, her mind would tell her. “Your failure to comply will kill your mother.” Sometimes she resisted, and then, anxiously, called home to find her mother still alive. But her mind would then tell her: “Modern physics tells us that there are an infinite number of parallel worlds, and your inaction killed your mother in at least one of those worlds.”

She also experienced intense anxiety episodes, including full-blown panic attacks. These would occur when in situations where decisive, quick action was needed. She would freeze when either fight or flight was a better option. Her anxiety would also be evoked in reaction to her mother’s dramatically expressed reactions when Naomi told her something about her life that might have some intensity within it. In short, her mother worried a lot and had ‘catastrophic’ reactions. This panicked Naomi.

In a large sense, emotions lived her, rather than she ‘having’ emotions. Whatever she felt was her only reality. She was unable to engage in ‘perspective taking.’ In other words, if someone said an angry word to her, she would assume the person hated her (and always hated her) or that she deserved the anger, because she was totally repulsive and unlikeable, or she would flare up into rage, that such an awful person would treat her so badly. She was at the mercy of every emotion she had, positive and negative. Her world was 100% whatever emotion she was feeling.

For those who are clinically oriented, she fit within diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder, with a complex array of symptoms of anxiety: foreboding worries, panic attacks and obsessive-compulsive traits. Her symptomatology was pretty severe, especially with her current suicidal ideation. Regarding the latter, Naomi could only say, “I don’t know why. I just feel bad inside. Not ‘bad about’ anything, or that I’m a bad person. I just feel like I’m totally out of control, and I feel sick to my stomach and I just feel something bad will happen, that there’s something bad about me, bad in me, and then, if things go the slightest bit wrong between me and someone I care about, it just feels worse.” Had she a history of trauma, therapy would, in one sense, be ‘easier,’ because a common working theory would be that these symptoms and her personality structure would change for the better as she dealt with her trauma. She didn’t have such a history, however. Furthermore, she was NOT traumatized within her relationship. She had no jealousy towards Gloria’s other partners, and considered them all friends. She was not ‘groomed’ into the relationship, either. She had been in the alternate-sex community of this city for a couple of years, had a variety of relationships, and one evening struck up a conversation with Gloria in a bar. Gloria was open about her relationship(s) from the beginning: in fact her husband and both her lovers, one male and one female, were out for a night on the town. In addition to Gloria, Naomi also later became lovers with one of Gloria’s ‘secondaries,’ and in this relationship, Naomi was dominant.

For individuals suffering as Naomi did, a form of treatment called dialectical-behavioral therapy, developed by Dr. Marsh Linehan, is considered to be the gold-standard.5 This is a very labor-intensive team-based approach. I could certainly refer Naomi to a program using this methodology, but this would not be appropriate at the present moment. She was in a crisis situation, and we had a workable plan to keep her safe. What would it mean to her for me to simply shift her off to someone else without fulfilling my commitment to try to help her?

In our next session, we worked with several techniques that are both stand-alone methods and are integrated into the dialectical-behavioral model. First was cognitive therapy techniques, where one becomes aware of one’s irrational thinking patterns, which evoke emotional reactions that cause distress. Naomi’s obsessive-compulsive thoughts and fears of catastrophe resulting when she didn’t give in to them would be an exemplar of what are referred to as cognitive distortions, as in the children’s rhyme, “Step on a crack, break your mother’s back.” Secondly, I introduced her to relaxation exercises, based on the common theory that relaxation and mindfulness practices relieve both psychological as well as physical tension.

This approach was profoundly negative for Naomi, and we couldn’t chalk it up to the comforting idea (for the therapist, at least) that what we were doing usually takes some time to work. Naomi was so intelligent that she quickly understood the cognitive-behavioral therapy interventions, but had an answer for any of them. We lapsed into discussions about quantum physics and the multiverse, where her actions could cause catastrophe somewhere else. Her vision of the universe was spacious and vast, but the result of all of this was a narrowing of her life into a world of anxiety and fear. The central problem was that her emotions were so central to the way she processed information that they validated themselves—she had very strong physical reactions to her emotions, and they confirmed her catastrophic thoughts. How could her fears not be true when she felt so profoundly anxious?

One would think that the relaxation/mindfulness practices could help, but I observed, after an initial period where she blissfully smiled, that she became increasingly more anxious the more relaxed her body became, and she would startle, like a sentry who went to sleep at her post and was suddenly awakened by the sound of a shotgun being racked nearby. Our sessions were two hours—after observing how these interventions were causing her to spiral down into a despairing crisis state, made all the worse by her feeling like a failure because these interventions sounded like they should help, we stopped. We took a walk through her neighborhood, and said little. Returning to her residence, we said, in overlapping sentences, “That didn’t work, did it?” After a final check-in with her that even though her suicidal thoughts had intensified after this session, she assured me that she would not act upon them, and reiterated a safety plan on whom to call if she felt helpless or in an emergency state, and what she should say and do. We agreed to meet in a week’s time, and I promised to give some thought as to what might help.

I spent the week thinking about shibari. This was, in fact, one of the few things in Naomi’s life that she took pride in—more than that, she felt it was a necessity. She explained that Gloria did not do torturous bindings—although some of them might look so to an observer. In fact, the ropes and her body became one sinuous entity; she melded herself into the bindings in a way that she felt free, often weightless. Because of her natural flexibility, nurtured by physical training, she could be comfortable in arrangements that were impossible to most people.

And it came to me that this was the one place that she could relax. She did not have to be self-supporting, all the while buffeted and prodded by a world—that world we all live in—full of stress, fear, anxiety and the requirement to make choices that can change the course of an hour, a day, even one’s life. The reader might wonder why the aforementioned relaxation techniques did not help her—maybe, they might suggest, she should try some alternative relaxation methods, like swimming, or even a sensory-deprivation tank. This would be a misunderstanding of the problem. What shibari provided was support. No matter what she did—whether she stretched or contracted, twisted or coiled, relaxed or tensed—she was held and contained. Shibari was the one experience in her life where she felt safe. But it required another person and this created dependency: not only was the support—the ropes—external, so was the agency. Without Gloria and all that went with her, including her ‘slave’ collar and small cage to sleep in, Naomi could not feel safe.

Which led me to think of swaddling. Consider the experience of birth. One is thrust from Heaven itself, a place of perfect nurturance and security into this terrible world, to experience cold harsh air, bright light, jarring noise: hunger, thirst, aloneness. And one’s limbs fly about, not in one’s control. One is suddenly helpless in a chaotic environment, feeling a part of that chaos oneself. Swaddling binds the baby into security, wrapped into a state as close to a return to the safety of the womb as it is possible to be. For Naomi, at least, shibari was swaddling. But one cannot live as a full, mature human being, dependent on being swaddled. One must be able to sustain oneself without being wrapped. Yet for Naomi, whatever state she was in soon became intolerable—she was like a baby who could not settle. She couldn’t stand it when she was tense, and she couldn’t stand it when she was relaxed. Since any experience would evoke tension or relaxation, in varying degrees, then any experience was, in a sense, an assault—it made her feel something, and whatever that was, she did not ask for it. She had no voluntary control over her experiences— paradoxically, only with Gloria, bound and helpless, could she feel in control, because she had constant support throughout.

At our next meeting, I presented baduanjin. I did not do this in some kind of ‘stealth therapeutic intervention,’ teaching the exercises as unspoken physical metaphors, where, theoretically, the improvement happens unconsciously—I find that this kind of intervention is often arrogant, disrespectful to the other person’s autonomy. Rather, I explained my thinking over the past week, and suggested that I teach her baduanjin in a particular style, much as I described in the last section. We would do the exercises in a way that she would tense to the degree that they were ‘intolerable.’ Then, she would continue the movement increasingly relaxing. She had already told me that she often felt, when relaxed, that she would crumble to pieces, or simply explode, because she “couldn’t hold herself together.” Therefore, when relaxation became ‘intolerable,’ she could continue the cycle of the movements, incrementally increasing the tension.

What I hoped for her was that she would have the experience of managing tension and release within her body, according to her will, and that she would apply this to ‘tension’ and ‘release’ within her thinking process and emotional reactions. By doing this alone, she would not be dependent upon another person for her sense of well-being. This applied not only to Gloria, but also to me—I taught her the movements, two each week, but it was up to her to practice them on her own. Finally, because these exercises were associated with martial arts practice, something she did not share with Gloria, she was able to separate the sensations she experienced in the practice of baduanjin from desire, pleasure, yearning, love: all the feelings immediately evoked in the presence of her lover and what they were doing or not doing.

Naomi and I would spend ten minutes at the end of each session debriefing the lesson: if she had any difficulties, and if any thoughts arose that she wanted to discuss with me. She stopped having suicidal thoughts sometime between the fourth and fifth week.

We completed the eight baduanjin exercises on week six, and we decided to schedule her next session two weeks later, so that she would be able to train and refine what she had learned. Of course, she as welcome to contact me if she was in any psychological distress, or had technical questions on any of the exercises.

On the seventh session, we ran through all eight forms, which she did creditably. She was not excellent from a martial arts training standpoint, nor was she doing the exercises in a manner that would best serve the development of qi (‘intangible vital energy’) from a classical Chinese standpoint. However, she was doing the exercises excellently for her purpose: she gracefully moved from one position to another, at some points exerting such intense tension in one position or another that her body would clench and shake. At other points, she moved through intense tension and then, semi-relaxed, creating a flexible tensile suppleness. Occasionally, she would explore structurelessness – letting the form ‘deflate’ or ‘collapse,’ and then, she would coil herself back into the form, like a snake rising up from slumber.

After fifteen minutes, she sat down and said, “I think we are good. I don’t think I need to do any more work with you.” When I asked her why, she told the following story.

“Gloria and I took a motorcycle ride the other day. She hit something slick and we slammed into a telephone pole. I got thrown clear onto some grass, and other than a few bruises (she pulled up a sleeve to show me one arm), I wasn’t hurt at all. Gloria was semi-conscious, and she had a broken collarbone as well. She was moaning, and there was blood leaking out from under her helmet. Ordinarily, this is where I’d have a meltdown. The woman I love was in pain, she was injured and I didn’t know how badly she was hurt. But instead of my usual freakout, I just rode it all. I held her down with one hand lightly on her chest, so she wouldn’t move, and I talked to her like she was a scared child: ‘It’s all right, love. I’m right here. I’m gonna get help. Don’t move, baby.’ I knelt with my knees on each side of her head, so she couldn’t turn—I didn’t know if her neck was broken. I kept her helmet on, because I didn’t want to twist her neck that way either, and anyway, I didn’t know if the pressure of the helmet was keeping some wound together. At the same time, I was thumbing 911 on my cellphone, and I called to a guy who was just standing there, and told him to tell me the streets at the intersection so I could tell the emergency people, and then I ordered him to gently hold Gloria’s legs. I told 911 where we were, and they came, and took Gloria to the emergency room, and checked me out as well. I called Gloria’s husband and told him he needed to get to the hospital—he started freaking out, and I told him just what I needed to say to calm him down. Gloria’s got this beautiful Ducatti, so I called to have it picked up, so no one would steal it, and I talked with the police when they came, and then went to the hospital. Gloria was OK: the head wound wasn’t bad, and her spine was fine. No concussion either. I was fine. So then, that night, my mom called. And she asked how my day was. Like I told you, my mom is super dramatic, and she freaks out at things and that freaks me out. So, I was just about to tell her what happened, and then I thought, ‘I only need to tell her what I want to.’ So I said to her, ‘Mom, I had a great day. How about you.’ So, Ellis, I think we are done. Thank you.”

About three months later, I ran into Gloria at a coffee shop. She asked me to step outside and she said, “I want to thank you. I know you can’t talk about Naomi from your side, but she’s doing great. About two weeks ago, she got the family together, took a huge bolt cutter and cut off her collar. Things have changed for her and us, but it really seems good. She’s like a new star in the community—she’s happy, she’s brave, and she has so many girls who want to be her lover . . .and guys too. We aren’t the same, but I’m good with that, and she’s so good for hersef.”

Just Anecdotes?

Perhaps the details of these stories are so unusual that some readers may be distracted from the actual work that went on. Furthermore, it’s ‘just a few anecdotes.’ That’s true—it’s not a research study. But when it seemed suitable, I continued to work this way with others. Were one to take my work further, doing further research on using baduanjin or a similar methodology in circumstances much like the case-accounts above, one would need:

Differential sorting,‘ so that the researcher is sure that she or he has a cohort of incarcerated youth, or people struggling with emotional reactivity, such as in the cases above, or another cohort entirely.

Several research cohorts. One would need to standardize the practice of a specific set of baduanjin for the study. Or, one could choose two or more different baduanjin methodologies to compare. Finally, one could add a different type of exercise, anything from yoga to such things as body-weight calisthenics to compare rates of improvement.

A consideration of teachers. Will differences in teacher personality or style of teaching effect rates of improvements. In other words, is it the messenger or the message?

A Conundrum

Millions of people practice baduanjin, and other similar qigongs. There are claims of benefits, some researched-backed, but almost all concern physical ailments. Given my accounts, shouldn’t millions have benefited in ways similar to what I have described? Given that no one can assert that those practicing qigong or other similar methods, like taijiquan, are psychologically more balanced than those who do not, there is something missing. Baduanjin is not a panacea, something that we could, for example, institute in the public school system and bring about a utopia of well-adjusted children, psychologically balanced, even healed from trauma. Could it be that it is a product of the practitioner: me? That’s certainly an attractive idea, at least as far as I am concerned, and quite pleased that you suggested it, but being as ruthless as I can about myself, I can confidently assert that this is not so. I have a memory-list longer than my arm of therapeutic encounters that were flat, and worse, that failed. I’m not that special.

So, if it is not the method alone, and we cannot merely the magical charisma of the practitioner, what is left? Intention. I did not sneak this methodology under the radar, like such paradoxical methods as Milton Erickson’s hypnotherapy or neuro-linguistic programing. I was open about what I was trying to offer, how I thought it might help, and what the client had to do. This doesn’t require a manifesto—all I said to the youth at the detention center was, “Don’t you hate it when someone makes you mad? Etc.”

What I do stand by is the theoretical construct, that the ability to manage tension-and-release within oneself, and between oneself and others is a crucial skill, and practicing baduanjin is a great modality to achieve this. But what it requires is an individual who has focused his or her mind upon this goal: they do not focus on becoming a martial arts athlete, of healing oneself of physical ailments, of learning a really elegant form of Chinese exercise—all of which are possible. They focus on using baduanjin as a learning tool.

Therefore, as best as I can tell, here are the essential components required of an instructor that would make baduanjin a vehicle towards achieving greater psychological integrity (I would note that Carola Schmid, mentioned above, shares these components I enumerate below, though her modality—Ashtanga Yoga—was different:

The instructor must be highly skilled in baduanjin - what use is a method that, if taught improperly, could cause injuries (one can, for example, tense the arms so much that one damages the attachment points of the ligaments and tendons of the elbows - I did this to myself when I was trying to learn this skill when I was improperly taught).

The instructor must be well-educated in psychology, particularly the psychology of people in extreme states, and comfortable within herself or himself when face-to-face with a person who is experiencing desperation.

The instructor must be able to articulate the concept of management of tension-and-release.

The instructor must be able to clearly link this concept, for the client, to his or her life-situation. In doing so, the instructor must be able to manage his or her own tendency to engage in other therapeutic interventions, to gather too much life-story (which can activate strong emotions within the client). In other words, the instructor must be disciplined enough to not get captivated by the life-story itself, and instead, look for patterns which serve to illuminate things for the client rather than satisfy other needs (be it telling the need or expectation that success in therapy requires telling the whole story on the part of the client, or engaging in the endlessly fascinating process of therapy itself, for both individuals).

The client must be able to focus herself or himself, through intention, to practice these exercises in order to master a new life skill, which will reverberate through his or her entire existence. The details of their life, the incidents, the history and situations they find themselves will then be met with this new skill-set, without the necessity of the mediating presence of a therapist, or anyone else, for that matter.

This substack is free, and will continue to be so. As a professional writer, I do hope to have my work supported, so for those who want to do so, here’s a far less expensive way than a paid substack subscription, one that will truly be welcome - please buy one of my books. My general book website is HERE. When an essay, like this one, is directly related to specific work I have done, I will add a DIRECT link.

More limited versions of this essay were previously published on my Kogenbudo blog as well as a compilation published by the European Academy of Biopsychosocial Health.

Cheng, Fung Kei (2015) Effects of Baduanjin on Mental Health: A Comprehensive Review. In: Journal of Bodywork & Movement Therapies, Volume 19, Issue 1, pp. 138-149.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fc/M%C3%A4dchenfaenger-Funktion.png

Redlinux, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

From a research perspective, it is obvious that Ms. Schmid’s involvement complicates this account, in terms of making definitive pronouncements as to baduanjin’s effectiveness alone (or Astanga Yoga, for that matter).

Linehan, Marsha, PdD, (1993) Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder The Guilford Press; Illustrated edition